Had Yogi Berra applied his considerable talent to marketing rather than baseball (I know, again with the baseball posts), no doubt he would have called site retargeting “deja vu all over again.”

For those of you unfamiliar with site retargeting, you no doubt have seen its effects. Ever visit a site and then see display ads for it on other sites? More likely than not, your visit to the site resulted in the placement of a cookie in your browser that allowed third-party sites, via an advertising network, to serve up ads related to that visit.

For those of you unfamiliar with Yogi Berra, he played catcher better than any ballplayer before, during or since his playing years. You can shut up, Johnny Bench.

Back to marketing. Site retargeting offers marketers a real chance to deliver an engaging, truly translinear experience to prospects and customers alike. Problem is, they usually don’t. So today, I’d like to share my point-of-view on the topic.

First off, let me address the privacy issue. Many privacy advocates find site retargeting a violation of basic privacy principles. These critics do, in fact, have a point. After all, many consumers may not wish to have sites follow them around. As with most online tactics, however, site retargeting works when it avoids the creep factor. Just as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said about pornography, we can’t easily define the creep factor, but we sure know when we see it.

Let’s focus instead on what we might legalistically call “fair and appropriate use” of site retargeting. Let’s imagine, say, that you’ve shopped for bikes and spent some time on a manufacturer’s site perusing their wares.

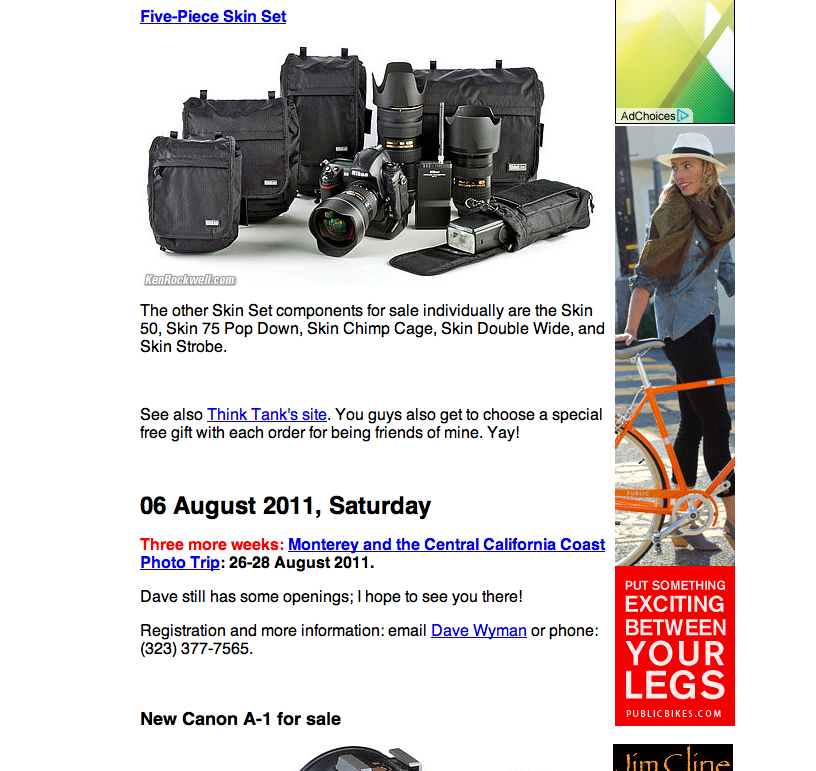

You might leave the site without taking any action, only to find an ad like this on a completely unrelated site:

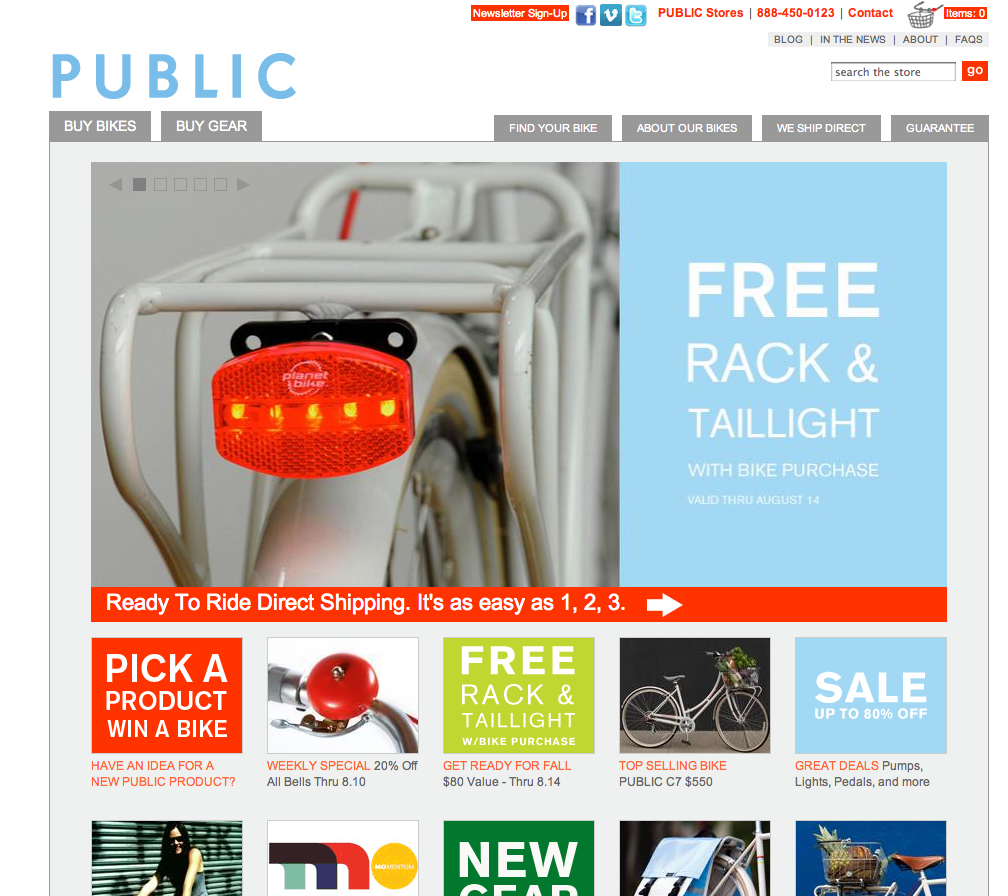

Let’s assume that this retargeting does not creep you out. So you click on the ad which takes you here:

Nifty, right?

Well, yes. However, think of what the bike manufacturer could have done. I used this example because I did, in fact, browse this site (disclosure: I am always shopping for my next bike and I bought a nifty pair of faux-cork handlebar grips from Public in June. Also, if my wife is reading, of course I’m not shopping shopping for a new bike. Just looking, OK?). I did get served the ad above and I did visit. A few times. Hey, Public makes some cool bikes.

Here’s what didn’t happen. The offer above (free rack & tail light with bike purchase) never changed, no matter how many times I clicked on the ad.

Direct-marketing old-timers like to say “it’s never too early to make the next sale.” Indeed, on the first return trip to the site, it made sense to serve up a sale-driven ad. But after that, might one reasonably assume that my visits were less and less likely to result in a sale, especially if I never clicked on the offer?

I would argue that Public wasted several exposures on me that they could have used to better effect. For instance, after the first visit or two, the lead offer could have changed to drive some sort of long-term engagement, such as the offer to receive brand updates via email or social networking. They could have directed me to a local store (assuming the ability to look up the IP address) or to their HQ in San Francisco. They could have directed me to articles about the brand.

Granted, Public bikes ain’t Procter & Gamble. They have relatively few resources at their command. However, most large marketers seem to fail in this respect as well. Few marketers think beyond that initial return trip to chart out a longer-term engagement with the individual.

At the same time, marketers might consider it a waste of time to plan for multiple return trips because the majority of return visitors will return only once. Fair enough, but for a considered purchase such as a car or even a bicycle (in may case, at any rate), many visitors will make return trips. Marketers, then, should anticipate what additional visits mean by way of site path analysis or other research.

Now, as Yogi would have said:

a) When you come to the fork in the road, take it

b) It ain’t over ‘til it’s over

c) You can observe a lot just by watching

d) All of the above

Answer: D. Yogi said lots.

For those of you unfamiliar with site retargeting, you no doubt have seen its effects. Ever visit a site and then see display ads for it on other sites? More likely than not, your visit to the site resulted in the placement of a cookie in your browser that allowed third-party sites, via an advertising network, to serve up ads related to that visit.

For those of you unfamiliar with Yogi Berra, he played catcher better than any ballplayer before, during or since his playing years. You can shut up, Johnny Bench.

Back to marketing. Site retargeting offers marketers a real chance to deliver an engaging, truly translinear experience to prospects and customers alike. Problem is, they usually don’t. So today, I’d like to share my point-of-view on the topic.

First off, let me address the privacy issue. Many privacy advocates find site retargeting a violation of basic privacy principles. These critics do, in fact, have a point. After all, many consumers may not wish to have sites follow them around. As with most online tactics, however, site retargeting works when it avoids the creep factor. Just as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said about pornography, we can’t easily define the creep factor, but we sure know when we see it.

Let’s focus instead on what we might legalistically call “fair and appropriate use” of site retargeting. Let’s imagine, say, that you’ve shopped for bikes and spent some time on a manufacturer’s site perusing their wares.

Is fetching, no?

You might leave the site without taking any action, only to find an ad like this on a completely unrelated site:

Let’s assume that this retargeting does not creep you out. So you click on the ad which takes you here:

Nifty, right?

Well, yes. However, think of what the bike manufacturer could have done. I used this example because I did, in fact, browse this site (disclosure: I am always shopping for my next bike and I bought a nifty pair of faux-cork handlebar grips from Public in June. Also, if my wife is reading, of course I’m not shopping shopping for a new bike. Just looking, OK?). I did get served the ad above and I did visit. A few times. Hey, Public makes some cool bikes.

Here’s what didn’t happen. The offer above (free rack & tail light with bike purchase) never changed, no matter how many times I clicked on the ad.

Direct-marketing old-timers like to say “it’s never too early to make the next sale.” Indeed, on the first return trip to the site, it made sense to serve up a sale-driven ad. But after that, might one reasonably assume that my visits were less and less likely to result in a sale, especially if I never clicked on the offer?

I would argue that Public wasted several exposures on me that they could have used to better effect. For instance, after the first visit or two, the lead offer could have changed to drive some sort of long-term engagement, such as the offer to receive brand updates via email or social networking. They could have directed me to a local store (assuming the ability to look up the IP address) or to their HQ in San Francisco. They could have directed me to articles about the brand.

Granted, Public bikes ain’t Procter & Gamble. They have relatively few resources at their command. However, most large marketers seem to fail in this respect as well. Few marketers think beyond that initial return trip to chart out a longer-term engagement with the individual.

At the same time, marketers might consider it a waste of time to plan for multiple return trips because the majority of return visitors will return only once. Fair enough, but for a considered purchase such as a car or even a bicycle (in may case, at any rate), many visitors will make return trips. Marketers, then, should anticipate what additional visits mean by way of site path analysis or other research.

Now, as Yogi would have said:

a) When you come to the fork in the road, take it

b) It ain’t over ‘til it’s over

c) You can observe a lot just by watching

d) All of the above

Answer: D. Yogi said lots.

Yogi might also have said about some websites: "nobody goes there anymore - it's too crowded."

ReplyDelete